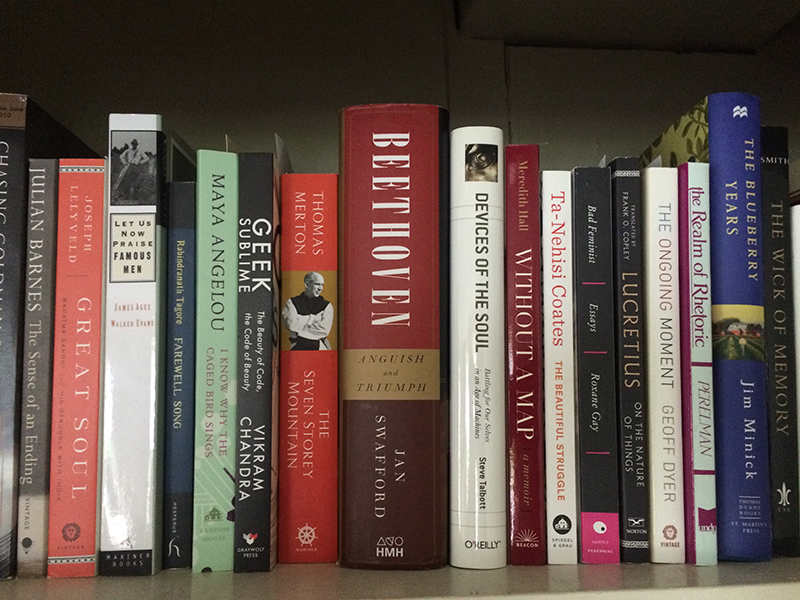

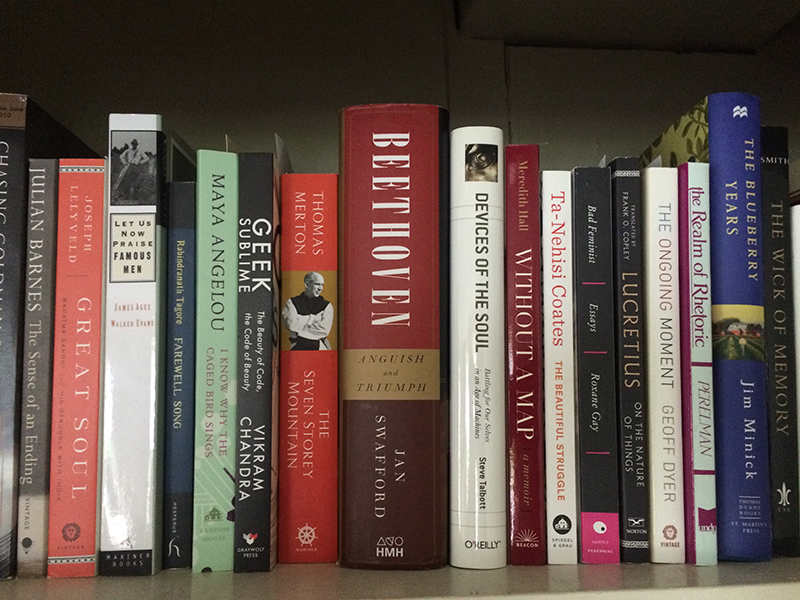

Not pictured: The Guermantes Way by Proust and Destiny and Desire by Carlos Fuentes.

Not pictured: The Guermantes Way by Proust and Destiny and Desire by Carlos Fuentes.

From The Paris Review:

I despise films that have a political agenda. Their intent is always to manipulate, to convince the viewer of their respective ideologies. Ideologies, however, are artistically uninteresting. I always say that if something can be reduced to one clear concept, it is artistically dead. If a single concept captures something, then everything has already been resolved—or so it appears, at least. Maybe that’s why I find it so hard to write synopses. I just cannot do it. If I were able to summarize a film in three sentences, I wouldn’t need to make it. Then I’d be a journalist, I’d get to the heart of the matter in those three sentences, and my readers would know what it’s all about, and that would be that. But that is not what I find interesting.

Look, life itself is the object of art. You aim to construct a parallel world in your novel or your play. The truly captivating thing is the story that unfolds between your protagonists. Of course, for somebody with political convictions—and we all have those—there is no way they aren’t going to seep into your artwork. Céline, for example, was a right-wing extremist. And that was visible in his work, but he still wasn’t completely inept as a writer. There are thousands of examples, from both the left and the right. At the academy, I always lecture on propagandistic films of various origins so as to sensitize my students to their particular way of functioning. In my films, however, politics happen only subcutaneously, and it is never my intention to say, Look, this is what I’m trying to tell you, now swallow it. My objective is a humanistic one—to enter into a dialogue with my viewers and to make them think. There isn’t much more you will be able to achieve in the dramatic arts. And frankly, I don’t know what else you should be able to achieve.

In Proust’s Within a Budding Grove, the painter Elstir tells Marcel:

“There is no man . . . however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived a life, the memory of which is so unpleasant to him that he would gladly expunge it. And yet he ought not entirely to regret it, because he cannot be certain that he has indeed become a wise man—so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise—unless he has passed through all the fatuous and unwholesome incarnations by which the ultimate stage must be preceded.

. . . We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can make for us, which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world.” (pp. 605-606)

The Iowa caucuses took place on Monday, James Joyce’s birthday was Tuesday, and late Tuesday night I found myself wondering how Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus would have covered the Iowa caucuses. The next day I quickly revised Joyce’s Portrait—from its baby-talk beginning to its diary ending—accordingly.

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road blocking traffic and making the buses shudder and honk because it was an election year and this was Iowa.

His father told him that story: his father had a hairy face. Not Hipster hairy. Vermont woodsy. Yuge.

He was baby tuckoo, cub reporter. The moocow came down the road where Betty Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt. A lady from NPR said it was yum.

Caucus was a funny word. First it made you feel cold. Then it made you scratch your head.

*

Rody Kickham was a decent fellow assigned to O’Malley but Nasty Roche from the Daily Caller was a stink. Nasty Roche had big hands and a little bow-tie. And one day he had asked:

—What is your name?

Stephen had answered: Stephen Dedalus.

Then Nasty Roche had said:

—What kind of a name is that? Are you an immigrant?

Then there was a tussle, and the big man with orange hair shouted: Go! Get him out of here!

*

Uncle Charles smoked such black twist that at last his nephew suggested to him to enjoy his morning smoke in a little outhouse back where the TV vans were running their generators.

—Damn me, said Mr Dedalus frankly, if I know how you can smoke such villainous awful tobacco. If you’re going to ride in the bus with us, you ought to consider vaping.

*

Stephen sat in the front bench of the barn. Father Arnall stood glumly at the podium flanked by Mr. Perkins and Senator Cruz. He wore about his shoulders a heavy cloak; his pale face was drawn and his voice broken with rheum. A PR flack rushed forward with tea and a lozenge and was brusquely waved away.

—Help me, my dear little brothers in Christ. Help me by your pious attention, by your own devotion. Banish from your minds all worldly thoughts and think only of the last things, death, judgment, hell, and heaven. Think only of defeating the liberals. Think only of curtailing wayward healthcare for slatternly women, and think mightily of bombing ISIS. Let the bombs rain down, yes, impinging the earth with terrible, ceaseless explosions, creating a lake of fire on earth, destroying every home in those accursed lands, incinerating every sinner, whether man, woman, or child, and consuming all things in a vast smoldering pit of suffering. This we ask through Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace.

—Amen! shouted the crowd.

Jeb Bush stood blinking at the door.

—Has anyone seen my bus? Sorry, wrong barn.

*

It would be a gloomy secret night. After early nightfall the yellow glow of the laptops would illuminate, here and there, in the lounge of the Residence Inn. He would follow a devious course up and down the aisles, circling always nearer and nearer in a tremor of fear and joy, until his feet led him suddenly round a dark corner to a table by an open electrical socket.

Facebook Messenger was already busy:

—Hello, Bertie, any good in your mind?

—Is that you, pigeon?

—OMG. Did you see Rasmussen?

A cold lucid indifference reigned in his soul. At his first sin he had felt a wave of vitality pass out of him and had feared to find his soul and reputation maimed by the excess. Instead the vital wave of contempt had receded: he had written a listicle and seen his Twitter followers spike.

Oh, corruptible soul!

*

A girl stood before him in midstream in the creek, alone and still, gazing outward. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh.

—Vegan PETA member protesting offshore drilling, whispered the fellow from Fox.

—Heavenly God! Cried Stephen. That’s weird!

*

Twitter updates from early February:

Away! Away!

The spell of white arms, red necks, and apple pie. Voices of kinsmen and natural-born citizens.

Visitors making ready to go, shaking their heads and talking of New Hampshire.

Hapless, bespectacled fellow searching for conveyance. —Has anyone seen it? It’s one of the larger vehicles here. With Jeb exclamation point on the side? Jay. Ee. Bee. No?

Clothes back from the Laundromat. Spare-changed again by HuffPo bloggers.

Welcome, O gig economy, wherein I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of expedience and to forge in the smithy of my soul 800 words by noon on Millennials.

O Chromebook battery pack, stand me now and ever in good stead!

The angélique was a 17th century type of theorbo, probably developed in Paris, featuring sixteen or seventeen strings. Like other theorbos, the angélique divided its strings into two sets. One set was tied to pegs over the neck and could be stopped by the left hand. The other set was tied to an extension away from the neck and could only be open plucked like the strings of a harp. Rather than being tuned in the Renaissance convention of fourths or the Baroque convention of thirds, the strings of the angélique were tuned in diatonic seconds.

This CD features theorbo virtuoso Jose Miguel Moreno playing a set of pieces by 17th century French composer Michel de Béthune for angélique. No 17th century angéliques survive; our knowledge of their design is largely a matter of conjecture. The liner notes of this CD mention transcription but are not explicit about what instrument the angélique music is being transcribed for. Presumably Moreno is playing these pieces on the French theorbo, or théorbe de pièces, for which the other compositions on this CD were written. Those pieces include works by de Visee, Forqueray, Lully, and Marais.

The liner notes tell us that “one of the most outstanding characteristic of French music for plucked-string instruments is a certain noble serene gravity.” I think that phrase nicely captures the feeling of this recording. The mood is pensive, the playing well articulated and soulful.

Recommended.

Pièces pour Théorbo Français: Music by Béthune, Visée, Lully et al.

by José Miguel Moreno

I had just stepped away from a simmering saucepan when our oldest popped into the kitchen and asked, “How far away is dinner?”

I squinted. “I’m guessing about eight feet.”

Both our girls are expert at rolling their eyes.